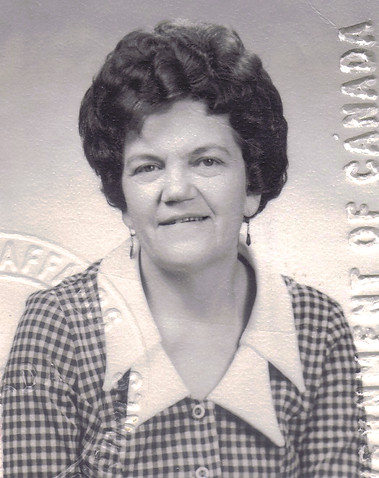

Janina (Kuzio) LANG

(Janina's story was originally published on the Canadian Polish Historical Society of Edmonton, Alberta website

and is repeated here with their permission.

See https://www.cphsalberta.com/)

____________________________________________________

I was born on April 2nd, 1930 in the settlement of Nowosiolki, in the district of Przemysl, in the voivoship of Lwow. My parents - Marianna, nee Rosada, and Jozef Kuzio - were married on September 26, 1926 in France, in the town of Ville de Lievin. It was a mining settlement, where many Poles worked in the nearby coalmines. In 1929, my parents returned to Poland, where they ran a farm that my father bought from Count Stanilaw Adam Stadnicki in the settlement of Nowosilki. They had a large house where I was born and where I spent almost ten years of a happy childhood. My sister Cecylia was born in 1932. Before the outbreak of World War II, I had completed 2 grades in the local elementary school.

Our lives changed dramatically when the Soviet troops invaded the eastern Polish territories. Our village and the entire region found itself under Soviet occupation. On February 10, 1940 my family was exiled to Siberia.

That fateful day at 4 in the morning, a sleigh, with three NKVD (Soviet Secret Police) officers in military uniform, pulled up in our yard. They told us to prepare for a journey “because there soon will be war here“ and we are being temporarily resettled to another location. One of them asked if my father had a gun. My father said that he had a pistol from the Austrian army. The NKVD officer ordered my father to bring the pistol and take it apart in front of him. My father obeyed and while my father was dismantling the weapon, a soldier was holding his gun to my father's temple, so that my father would not turn the pistol on them.

Meanwhile, my Mom was crying terribly. Neither I, then 9 years old, nor my seven-year-old sister, could understand what was going on. One of the soldiers, who was apparently a good man, tried to calm my mother. He advised her to take winter clothing. He helped us pack, and told my mother to pack her sewing machine as well. He told my father to take an ax, a saw and other tools that were in the house. My parents by then figured out where we were being relocated. It was to be Siberia. There was not much bread in the house because my mother was to do the baking on Saturday, and that was the day of our deportation

.

The railway station in Medica was 4 kilometers away. When were arrived at the station, there were already many people from the settlement. We were loaded onto a freight car, which was outfitted with double bunks. The top bunk was given to the children and the adults took the bottom ones, but there were so many people that there was not enough space for everyone. My parents took turns sleeping in the bunk. Once the freight car was filled up, the doors were locked and the only way to look outside was through a tiny, dirty window that was situated near the ceiling. We waited at the station, locked up, for three days until all those who were designated for deportation were brought to the station. From the other cars, we could hear the wailing of mothers and children. Inside the freight car, there was a small metal stove and a hole in the floor that served as a toilet. Blankets were hung around the opening in the floor, giving a semblance of privacy. Finally, the train began to move. This was the most terrible moment. Everyone started to pray and cry. That one collective moan stayed in my ears forever. To this day, I can hear it when I reminisce about that moment. I remember my mom crying nonstop. We could not calm her. On the third day of the trip, my mother half-asleep, (she slept sitting up) heard a voice speaking to her: "Do not cry, everything will be OK!" She believed the voice and stopped crying.

When we reached the city of Lwow, we were given some soup and firewood. More cars were attached to the train. I remember when one day, the train began to retreat. Some naive joy reigned in the car, we're going back to Poland. Meanwhile, the train reversed to allow a military transport to pass.

We travelled for three weeks, once forward, then back. People began to get sick. There was nothing to eat. Often the train would stop in the middle of nowhere. Sometimes we got a bit of some sort of soup, sometimes boiled water, and sometimes the train did not stop for 24 hours. Through a small window, we would lower a bucket in order to grab a bit of snow, which we then melted on the stove to have a drink of water.

Finally, on March 4 we arrived at Krasnoyarsk, where we were loaded onto trucks. After a three-day trip, we arrived at Pima of the Mansk region, in Novosibirsk oblast. There were two huge, long buildings with triple bunks; this had probably once been a prison. One of them became home to 500 people. The children took the top bunks, the middle ones were reserved for the youth, and the adults took the bottom bunks. The exiles began to get sick and die. Most of the victims were young people between the ages of 14 and 20. It happened that one day we buried 10 people. My mother fell seriously ill due to inflammation of the joints. As the older daughter, I had to take care of her. My sister Cela attended school, as it was mandatory. Dad was sent to work as a carpenter. When mother’s health improved, she went to work in the quarries. The Russian Government started to build railway tracks, and these stones were used in its construction. I started school, and every day after school I had to stand in line for bread. We got half a kilogram of bread a day (soaked in water to make it heavier) for each adult, and 300 grams for children. If the parents managed to reach their quota, they would get a serving of fish-head soup, with a few grains of hulled barley. About 6 kilometers from our settlement, there was a collective farm (kolkhoz), where my parents began to trade for flour, milk, a piece of bread or any other kind of food to survive.

We lived like that until ‘Amnesty’ was declared in the summer of 1941. The commander of our settlement called a meeting and announced that General Wladyslaw Sikorski had signed an agreement with the Soviet Union and that we are to be set free. We were informed that a Polish Army is being organized that will fight the Germans together with the Red Army. The Polish Army was being formed in the south of the Soviet Union in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. He told us that we were free to go if we wished.

Of course, we began to plan to go south immediately. First, we went to a neighboring collective farm, called Narew. My father went to work on the collective farm. Mom began to work as a seamstress, sewing padded winter jackets (kufajki), because she had her own sewing machine. That sewing machine saved my mom‘s life because she didn’t have to do heavy physical labour.

Working at the kolkhoz, we managed to dry some bread and save some money, my parents sold what they could and we hit the road. First, we hitched a ride on a truck to the train station, where we boarded a freight train to Novosibirsk. When we arrived at Novosibirsk, the station was already full of people with the same intentions. There was standing room only. My father, together with some of our neighbours from our settlement in Poland, tried to secure a passage out of Novosibirsk. Finally, after a week of waiting, they were able to buy a passage on a freight car with double bunks. There were 54 of us, and we travelled for 2 weeks. Often the train would stop in the middle of nowhere. Other times it would reverse to allow military transport trains to pass. There were instances where our freight car was detached from one train and attached to another.

Finally, we got to Osh (Kyrgyzstan), where we were directed to one of the kolkhoz. We moved in with another family into a house that belonged to the kolkhoz. My mother began working at the hospital, and father went to work in the kolkhoz. We were lucky that my mother got a job in a hospital, because my sister fell ill with typhoid fever and my mother, working in the hospital, was able to look after her.

After a short period, the men went to Jalal-Abad to join the Polish Army. Women and children stayed in the kolkhoz, waiting impatiently for news on when they can reunite with their husbands. Since they expected that the news would reach them any day now, my mom gave 2 weeks notice at the hospital. She did not receive permission so she quit, thinking that they could do nothing to her; after all she was a free person. Another Polish woman Mrs. Mucha followed my mom’s example. They soon found out that this was not that easy. The NKVD came and arrested both my mother and Mrs. Mucha, who had two small children (three and five years old). Both women were taken to court and sentenced to five years' imprisonment for unlawful abandonment of work. Both ended up in prison.

My sister Cecylia aged 9, and I aged 11, were left to fend for ourselves. We began working at the kolkhoz so that we would not be kicked out of the house and be deprived of food. When we met out quota, we received some flour. Threads from our mother sewing were exchanged for milk. We would make soup and take it to our mom in jail. Mrs. Mucha’s 2 children, who were in prison with their mother, were not given food. This was to force the mother to give up her children to so that they can be placed in an orphanage. This lasted two weeks, and any day now, the mother and children were to move to the prison in Osh. It was said that once you entered the prison in Osh you did not come out. However, God had other plans. Quite unexpectedly, my father came to take us to Jalal-Abad, where transport ships were leaving for Persia (Iran). It was the Saturday before Easter. Dad began to seek help for the 2 imprisoned women. He contacted the Polish authorities, and they were able to secure the release of my mother and Mrs. Mucha and her 2 children. They were freed on April 5, 1942. The joy, which we experienced, seeing our mother free cannot be expressed. Immediately, we left for to Jalal-Abad (Kyrgyzstan), where we waited another four months for the coveted transport to Persia. While in Jalal-Abad we were under the care of the Polish authorities and we were not starving as before. Life began to normalize somewhat. There was Polish school. The younger children were prepared and received first Holy Communion and older ones Confirmation. Bishop Gawlina gave us his blessings and administered the sacraments. Our dad was in the military and we lived in a tent. Leftover food from the army kitchens were given to us. Finally, at the beginning of August, 1942 we were loaded on ships and left from Krasnovodsk, a port on the Caspian Sea, on a 24 hour journey. Travelling in terrible conditions, we arrived in Pahlavi. Finally, we were free. Pahlevi was the first place of residence for refugees from the "inhuman land". Upon arrival, the first thing that we went through was delousing. Our hair was cut, we took a bath and now clean and refreshed, we walked down a long corridor and entered a "Clean Camp", where we were given clean clothes and food.

We stayed in Pahlavi for 3 weeks, after which we were sent to Teheran, to Camp # 1. Dad was in the army camp. In Tehran, the Polish delegation made sure that our living conditions were adequate. My mother enrolled me and my sister in Polish school, where I completed 4th grade in half a year. After 5 months we were moved to Achwaz, where I finished 5th grade, and my sister and I joined the Polish Girl Guides.

At the beginning of July 1943, we went to Karachi, India (now Pakistan). From there, families were sent to different places that were prepared by the representative of the Polish government in London. My family was sent to Africa. We sailed by ship through the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean. Because the sea voyage was dangerous, we travelled in a convoy of about 100 ships. The security of travelling in a convoy added courage in face of danger when our ship came upon a mine that left a gaping hole in the hull of the ship. The lifeboats were lowered, but somehow the crew managed to take appropriate action and we reached the port of Dar-Es-Salaam.

From the port, we rode the train through the jungle to port Juba. From there we sailed, on a small African ship, on the beautiful Lake Tanganyika to Mpulungu (now in Zambia). From this port, we were taken to a camp in Abercorn (Shamva), Northern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), where 550 people were placed in brick houses covered with elephant grass (sea grass). The camp was well prepared, having all possible amenities. We had a public school, hospital, church, and a community center. For high school, I went to Lusaka (Rhodesia). After a year in this school, we were moved to a school in Kidugali, which was housed in brick buildings of a former evangelical mission.

Our stay in Africa, after the horrible experiences of the "inhuman land" in Siberia, was the most beautiful period in our lives. It was there, on another continent, we had a substitute Poland during those 6 years. It was there that our characters were shaped, and it was there that we learned the love of God and country.

After the war, life in the Polish settlements in Africa continued to be relatively normal. Slowly, however, in the years 1947-1950 the settlements were liquidated.

My mother, sister, and I, left for the UK. My dad was waiting for us there. Finally, our family was together. From there we went to the transit camp in Stafford and, after 3 weeks, to Shobdon. This was our last transit camp because, after 6 months there, we left for Canada.

January 26, 1949, we arrived in Alberta. My parents went to work. Dad worked at the Mercoal mine near Edson, and I worked there for a year in a hotel. After losing my job, I moved to Edmonton. In Edmonton, I worked first in various restaurants, then in Simson- Sears, and the longest (17 years) in Woodword's Department Store.

In Edmonton, I met my future husband, Julian Lang. We got married 24 November 1951. Our life together worked out very well. We raised three children, two sons and a daughter (Henry, Ted and Helen). Now our children have their own families, and we enjoy our retirement and take great pride in our 10 grandchildren.

Most of my life has been associated with Edmonton, where I worked, raised my children and was involved in the Polish Community. I was a member of the Combatants Ladies Circle for 40 years, taking part in organizing various events to support the Polish Canadian Combatants (SPK). After the Combatants Ladies Circle was dissolved, I became a member of the Polish Canadian Combatants Society (SPK). I am a member of the Rosary Sodality Circle, as well as the St. Cecilia church choir at Holy Rosary Church, I also belong to a seniors’ choir group called "Polskie Kwiaty" .

Based on text supplied by Janina Lang and an interview by Zofia Kamela

Translated into English by Helen Fita

Unfortunately, no descriptions were provided for the photos

Copyright: Canadian Polish Historical Society of Edmonton, Alberta