Irena (Baranowska) EHRLICH

Excerpt from her book, tramslated from Polish

I was born on Dec 25, 1918 in Ciechanów near Warsaw, Poland. I come from Mazovia, but from the age of three my parents moved to the Vilnius region. My father had a job where we moved from place to place - Podbrodzie, Święciany, Bezdany. In 1939, were living in Bezdany, then in the town of Kinieliszki. I passed my secondary school-leaving examination in Vilnius in 1939, and in the fall I taught in a primary school.

Early in the morning of April 13, 1940, there was a knocking on the door and shouts in Russian: "wypniajtie!". Mom was petrified, and so was I. I had four sisters and one brother. Father had died in 1938. My youngest sibling was 10 years old. We were all petrified. There was very little time. We were only given half an hour to pack. We didn't even have any bread.

The deportees were gathered at the train station. People were very depressed. We were loaded into cattle wagons. A hole was drilled in the middle of the cattle car and this was made for sanitary purposes. At first, people were embarrassed, but later, when the hunger came and the children began to die, the embarrassment ceased.

The trip lasted two weeks. We were finally thrown out at a station in the small town of Bułajewo, somewhere in Kazakhstan, near Świerdłowska in Siberia. We were assigned to a collective farm called Oktiabersk. The people were dressed in gray, wityh shoes made of old tires. They watched us with interest because, unlike them, we were dressed very well. Their faces seemed to show respect and surprise. But when the NKVD appeared, they all disappeared immediately. We sat like that in the square for two days and nobody was interested in us. Finally, we were told that we were to apply for a job ourselves. We were left to our own fate. Finally, the kolkhoznik showed us a half-ruined mud hut. He demanded 50 rubles a month for rent. We accepted the offer and moved into the mud hut.

The next day we went to the nearby town of Bułajewa. We reported to the NKVD. I knew a little Belarusian and it turned out to be helpful in finding a job. We met a friend of mine, Topolska. She advised us to go to the village where there was an orphanage. We learned that it was very easy to get a divorce in Russia and the director of this orphanage was getting married for the sixth time. Thanks to the acquaintance with the director's last wife, we were hired. I was assigned to the kitchen, which was located in the annex of the orphanage. It was a good job. My sister was assigned to wash the floors. There were about 200 children in the orphanage. They were fed very modestly: for breakfast they had milk mixed with water, for dinner they had soup, potatoes and some noodles, and once a week a piece of meat that fit on one spoon.

One time, when I was on duty in the kitchen, hungry young boys aged 10 to 13 attacked the kitchen. Six were standing over me with knives in their hands: "Nanny, open up, or we'll slaughter you!". Terrified, I opened it to them. They took all the bread. I didn't have the strength to close the door. Mrs. Topolska - the main cook - came. I told her about the attack and after 15 minutes the NKVD appeared. Not only did they find the six boys who had stolen the bread without difficulty, they took all the boys to a correctional home. After this incident, all Poles were fired from work in the orphanage.

From then on, we walked to work for several kilometers every day. I remember when my mother and I were walking along the road on Christmas Day in 1940, a wagon was in front of us and at some point a sack of flour fell from it. We immediately buried it in the snow and we were glad that we would prepare a wonderful dinner for all the Poles in the camp. Unfortunately, the kolkhoznik realized it and took the flour from us.

We were always in a hurry to get to work, because for 15 minutes of delay we faced a year in prison! Mom got a good job making tar. I was assigned to clear the ditches where the pipes were buried. Work went smoothly until it was deep. It was hard to throw snow out of a deep ditch - it was falling off the shovel. I was desperate that I would not meet the quota, and there are small children at home waiting for bread. The norm was small - about 200 grams of bread per person per day. Mom gave me a ladder and advised me to load the snow into a bag and bring it to the surface. Despite this, I did not meet the quota. Our Christmas Eve in Niewieżka near Bułajewo was a hungry one. Mom met her quota and got those precious 200 grams of bread. She cut it into pieces, like a wafer. In the pillowcase, at the very bottom, we found some more flour, which we once exchanged in the kolkhoz for things brought from Poland. My sister Alinka did not work yet because she was too small. She cooked roasted bread in water from this flour. That was our first Christmas Eve in exile. There are a lot of sad memories.. I remembered Christmas Eve in Poland from early morning until 12 o'clock at night, when we went to Midnight Mass.

The next job we were assigned was the cultivation of cabbage, cucumbers and other vegetables for children in the orphanage. Somehow, these other vegetables never came, because there were no seeds.

The barracks we stayed in looked terrible. They were full of bugs. The floor was clay. They had to be cleaned first to make them habitable. Fiedzia, who was responsible for delivering water in a barrel, fell seriously ill, lay on the grass and trembled, seriously ill with malaria. Then the manager told me to take the position of "water carrier", with the assistance of a lame ox. You had to be able to speak to it to make it move. It only reacted to loud Russian curses. The job was to pour water into a barrel and, shouting, pull the ox by the bridle.

Soon they loaded us on trucks with our sacks, packed us back into cattle wagons and took us to the city of Akmolinsk. We were herded there to build a railway line. We learned that the war with Germany had broken out. Masses of people were concentrated to build this line. Work went on for 24 hours a day. We were assigned working hours from 2 am to 10 am. We poured sand out of the wagons and placed stones in cubic meters. In the morning everyone was very exhausted, we wanted to sleep and we could fall asleep leaning on a shovel. It happened to me once. The foreman of the brigadier suddenly shouted and I fell, terrified.

It was October and it was already very cold. People were dressed very lightly. We were concerned that we would all freeze here and that would be our end. The older ones sent the young ones to the NKVD to ask for warm boots and jackets, because it was impossible to work without them. I also went. In the office sat a large NKVD man in a tight uniform, with medals, as straight as a mannequin. He was smoking a good, fragrant cigarette. I remember he had a very thick, blooming nose

Such details are sometimes well remembered. We trembled like jelly, went to the desk and presented our case. And, surprisingly, he did not shout at us, but told us not to worry about clothes, because soon they would send us to Almaty, and it is warm there and we do not need clothes at all. Of course, we didn't believe a word, but it soon turned out that he was telling the truth.

were crammed into cattle wagons, and they gave us a few bags of frozen potatoes. There were also a few bags of stale flour. And so the journey to Almaty began. On the way, children began to die and elderly women became seriously ill. There weren't many men in our transport. There was only one in our car - Mr. Pieńk. He held on bravely, although the fourth child was dying in his arms. It was necessary for someone to bring hot water to the wagon - "kipiatok". Nobody had any warm clothes and the snow had already started falling. One of the ladies in our car, Mrs Świętorzecka, offered husband's shoes to the person who will take the position of the wagon commander, although they had holes in them, but were still usable. I took up this function and from then on, at every stop I went out in my shoes for the "kipiatok". It was actually our entire meal, because the pancakes made of stale flour were unedible and they smelled so bad that it was hard to breathe in the car. We were consoled that this journey would not last forever and one day we would get to Almaty.

At a large station in Orskoye, I suddenly saw something that made me think that I was hallucinating, that I was seriously ill. I saw a Polish soldier in a huge, fur hat with a Polish eagle. He had such a very short coat, three-quarters, but on the Russian cap there was a Polish eagle! I thought I must be hallucinating after all! I approached him and, holding buckets with "kipiatok" in my hands, looking at the soldier, I asked "are you really Polish, and the eagle on your hat is really a Polish eagle?" He looked at me, nodded, and said nothing. He seemed to think the same things about me as I did. He confirmed. I asked again if it was a real Polish eagle and how did it happen that here in Russia it has an eagle on its cap. He looked at me again and said: "And you don't know that the Polish army is already here?" Two buckets with the "kipiatok" fell out of my hands. I knelt in the snow, crossed myself and didn't know what to say. I was so happy that I suddenly became speechless. I couldn't even thank him. Finally, I regained my composure and choked out: "Could you please take me and my sister to the army?" "No, that's impossible," he replied. "Anyway, I do not decide. The chief of this transport is here, but I doubt that he will agree to take the ladies into the army. The boss was just coming. Also in a fur hat and also with an eagle. He had a bushy mustache, looked maybe forty, thoughtful, very considerate. I laid out my case to him. He asked where I was from. I told him it was from the Vilnius Region. His eyes brightened and he asked what city I had been to lately. "in Vilnius" I replied. Then he introduced himself: "Plawgo, I am". And he started scratching his head a lot. I prayed at that time that God would inspire him, that he would take us away. I showed him a whole train load of wagons loaded with Poles. And Mr. Plawgo agreed to take us to the army. I cannot express in words what was happening in the car. They shouted: "O Jesus, Maria, we thank You! They cried. Others were speechless, unable to utter a word! The Polish Army, the Polish Army, finally there!". My mother said goodbye to us, we said goodbye to the whole car and then, navigating under the carriages to confuse the NKVD, who were everywhere, we sneaked into the military transport. The sergeant made room for us, we were on one side of the car and the men on the other. They were burning wood on our side.

There was a pleasant warmth in the wagon. Mr. Plawgo encouraged us to make ourselves at home. He was also taken away with his family and maybe his children will also be looked after by someone like he is looking after us now. He reassured us so that we would not be afraid that he would look after us like a father. He said that poor Poles know how to respect women. Someone knocked on the door. The sergeant was scared that it was the NKVD, so he told us to hide behind a pile of trees. He opened the door and saw a woman in the snow, barefoot - our mother. She stretched out her weary hands and begged: "Little girls, come back, it is not appropriate for you to go with men in the same carriage. Whatever happens to us, let it happen, what God will give us! I want you to stay with me. Come back. , come back! We will get lost, you will go to the army, how will we find each other afterwards? Better together with the whole family! " Sergeant Plawgo began to get impatient, because he was afraid that the NKVD might come at any moment. "If the ladies want to listen to mom, please go out!" The sister could not stand the pressure and got out with her bundle. I was faced with a dramatic decision. In such moments, some strength dominates a person. I believed so much that I would be okay, that these people are the most honest in the world. I believed that I would get into the army, that I would be able to help my family and others. And I stayed.

I was assigned two English blankets and a royal dinner. I was given tobacco, even though I had not smoked any cigarettes at the time. There was various canned food in the transport, some jams. All this could be eaten without restriction. I thought it was a dream, that it was impossible for something like this to happen. So suddenly: yesterday you were hungry, today you are full. After a sumptuous dinner, I lay down in my seat, wrapped it in new, fragrant blankets. But my conscience was starting to bother me terribly. And once it seemed to me that I did the right thing, then again that I did something terrible. How could I leave my mother and sister and brother and all those people from our transport. After all, I was carrying water, I have shoes from Mrs. Świętorzecka. There are no more shoes in the wagon, who will carry the water? Incredible struggle of conscience. I had the rosary twisted on my wrist, I tried to pray, but the prayer broke. Finally, weary, I fell asleep.

We traveled for a week. Finally, the train stopped in Totskoye. An order came that we should not go any further. I wanted to get to Buzuluk, to the Polish army! I was very worried. I didn't know what to do with myself. The soldiers did not feel sorry for me because they had their own affairs. I retreated slightly from the wagon so that the NKVD would not see me.

Sergeant Plawgo told me to go to Totskoye, there is also the Polish army there, there are also women. And I made up my mind. I said goodbye to him. This man remained in my memory for life, but it is a pity that I never met him again.

I wanted to go to Totskoye immediately. The night was moonlit. I was walking and at one point I heard the howling of wolves. I felt numb. I started praying and quickened my pace. The wind picked up and it started to snow. The howling grew louder. I wasn't sure if I was going in the right direction. Finally, I saw the lights that turned out to be the camp. I came to a building with a sign simply written Tock, not Totskoye. I entered the camp grounds and found where the volunteers were. The commandant, dressed in beautiful English pajamas, ate bread fried with sugar. It smelled lovely. I stood on the threshold and said quietly that I would like to join the army. The commandant stopped eating bread for a while and was very angry with me. First of all, I shouldn't have come in here without going through quarantine. Besides, there are no jobs left, and the fact that I was walking at night through a forest with wolves shows that I am not in my right mind and would not be a good soldier. She told me to leave and go back to the station in Totskoye. I had no other choice. The wolves did not howl anymore. I got to the train station and sat down in the corner by the stove. A major approached me and suggested that I should not go to the army. He himself is without family, he will soon go to Kuybyshev to buy musical instruments. She has a small room and will take care of me. And why am I going to the army anyway? He told me that Buzuluk is even worse. He looked at me and said: "my friend is probably hungry?" He went to see if there was anything to eat at the station. It was enough for me to take advantage of his absence and run away. I met another gendarme. He was very happy because he found his wife and two of his children. I told him that I was going to Buzuluk. There were no trains in that direction anymore. He suggested that I stay overnight with his wife, who really welcomed me very warmly. Her name was Szmit. Later we met in England while she was working at the hospital.

The next day the gendarme tried to force me into the wagon. This way I managed to get to Buzuluk. Volunteers were already on duty there. So they were telling the truth: there is a Polish army! How many troops were there - how many people who dreamed of joining the army! They came wrapped in old quilts, blankets, whoever had what! Nobody has ever seen such human material for the army before. Finally, I found out that I was to report to the staff, which was located in a beautiful imperial building. The rest of the buildings were small cottages in the Russian style. In the past, landowners probably lived in the imperial building, later it was occupied by the Komsomol and now by the headquarters of the Polish army. The Polish banner was flown at the front. I thought my heart would break with joy. I went inside. There was a buzz, the humming of the typewriters, the radio messages were heard. Polish language everywhere - what a wonderful feeling!

I was told that the women volunteers were quartered at Półtoromajska Street and that I was to go there. I wasn't accepted into the army right away. The commander said there was no room and that I should go back to the railway station. In the meantime, the inspector, Mrs. Puchawska, who also came from Vilnius, arrived. I don't know if it was a miracle, a second miracle, but she told hrt to receive me and she left. The commandant told me that I would not have any corner, not even to sit down. And there was indeed no room. I was finally given a seat at the door. I slept there for two weeks. People were walking over me at night, trying to get outside with a physiological need. I was happy, so happy that I got this place, this corner. We got three meals a day. A friend of mine died of typhus on the upper bunk. I got her place. At first I was happy that I was so warm, then my conscience started bothering me that my friend died and you, stupid, are happy. Later, I was assigned to an educational platoon in the company of Jadwiga Domańska. The beautiful lady was sitting on the bed. I reported: "Mrs. Commander, volunteer Irena Baranowska reports her assignment to the educational platoon." I will never forget her beautiful smile. Back then, people needed that smile and that little bit of a human heart so badly.

Mrs. Domańska was later in Winnipeg. I told her everything, but she couldn't remember. Only after telling her the details did she recall some of the situations. We went to Kołtubianka as day-room workers. The education section didn't have much to do. The soldiers lived in tents, their backs frozen to the walls, and the moon could be seen through the canvas of the tent. There was no place for educational work there.

Then we were transferred to Kermine. The Kermine camp went down in the history of the Polish army as a death camp. Malaria and typhus raged there. My husband later wrote a book about infectious diseases in the camps in the USSR. In Kermine, we organized trips for soldiers, gave lectures, caught Russian radio messages, translated them into Polish and passed them on to the soldiers. My cooperation with Mrs. Domańska ended. I was assigned to the Air Force.

We left Kermine. It was early spring 1942. We were taken by train to the crossing point in Krasnowodsk. From there by ship to Pahlavi to Iraq. In Iraq, I worked in the army headquarters. Then we were transported to Baghdad. My sister worked there in a hospital. My mother and her youngest sisters were sent to resettlement camps in Africa. My brother joined the Junaks. He recovered from typhus, then was assigned to Air Force in England.

We managed to establish contact with the whole family. I met my sister in Rehovot. At Cassa Massina in Egypt, I worked in the Emergency Room. My commandant, Mrs. Moroziewicz, assigned me to the staff. The next stage was Italy. First to Barlett, then to Ancona. I remember Ancona gave the impression of a city of the dead. Chickens were just running around the streets. The ceiling-mounted chandelier rang from artillery shots. The sappers showed us a way free from min. In Ancona, I worked in an emergency room in a hospital and it was there that I met my future husband. At his instigation, I enrolled in a nursing course and started to work in this profession. There is probably nothing nicer in the world than the situation when a terribly ill patient is admitted to the hospital, and then a healthy person is released.

We had our hands full at the military hospital. The nurses started the day with injections. Then sulfa drugs for stomach patients. Dressings, medical inspection. The nurses wrote down the doctor's remarks in the order book. Same routine in the afternoon. Watching meals for the sick. Those suffering from contagious disease suffered a lot. There were many sick with venereal diseases. We felt sorry for them. There were cases of tuberculosis and malaria.

I got married on November 25, 1945. We were married in the hospital chapel by Fr. Wróbel. My husband moved to Conegliano and I moved to Rimini. I worked there in the infectious diseases department. The nurses were very busy. It happened that for one nurse there were up to 100 wounded and sick to be served. Paramedics often helped with some functions, such as taking temperature and even injections.

I remember that one day I went with the English captain to Loreto to buy an Our Lady of Loreto medallion for my mother. On the way back, the captain lost control of the steering wheel and the car turned upside down. An army unit passed the road and they helped restore our car to its normal position. Everyone burst out laughing when they saw me and the captain under the overturned car. In the meantime, a report about a road crash went to the hospital. Virtually nothing happened to me apart from minor bruises. I returned quickly to the hospital. On the wall was a poster: "Nurse Irena Died in a Car Accident." A patient who saw me in the nursing uniform screamed in terror as if he had seen a ghost.

Our hospital, the 6th Military Hospital, was finally transferred to England. My husband also got a transfer there. In England, a decision was made to emigrate to Canada, where my husband's friend from the University of Lviv was already there. I went to London with my husband. We started our efforts, medical examinations and diploma recognition. Canadian law required new exams and a new internship in the hospital.

We came to Saskatchewan. People were friendlier here than in England. We live in North Battlefort. My husband started studying psychiatry again. The snow did not scare us. We received furniture and a house. We were delighted. There were many doctors from different countries in the hospital. We organized social meetings every Saturday and Sunday. This is how we survived 16 years in one place. Our first daughter was born to us in England, the second, red-haired Jolanta and Ewelinka were born in North Battlefort, Saskatchewan. My husband worked in this hospital until the end of his career as a deputy superintendent. He worked a lot in research and had a wide range of interests. He was in touch with Czapski and Giedroyc from the Literary Institute in Paris. He left behind many notes that could certainly be used. He left behind, written on birch bark, a short memoir from prison times and other diaries. I am also writing down my memories.

In 1965 the family moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, where we joined the Polish Combatants Association #13, and Legion Branch #34 A. Mynarski,V.C. In 1968, the family was greatly saddened by the passing of my husband after a long illness. I served as librarian in the Polish Combatants Branch, and taught Polish school in the parishes of St. Andrew Bobola, St. John Cantius, and Holy Ghost Church. I served as a member of the Board and Secretary for the Polish Combatants Association, as well as the Polish newspaper Czas, and the Canadian Polish Manor Residents’ Association.

At age 92, I published Pamiętnik Ireny about my wartime experiences. Throughout the changes and challenges of her life, I never wavered in my dedication to Polish culture and history, and my belief in the freedom of the homeland I held foremost in my heart.

I was decorated for service and valour at Monte Cassino, and also received the Italy Star, War Medal and Defence Medal. I remain devoted to the family history I shared with my sisters Jadwiga, Alina and Krystyna and younger brother Edmund.

Note: Irena passed away at the age of 102, on September 7, 2021.

Irena in the Polish 2nd Corps

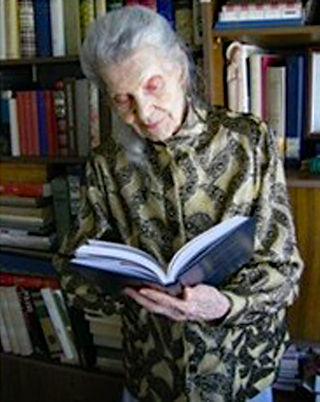

Irena in Winnipeg

Copyright: Ehrlich family