Aniela RUSZEL-PARKITNA

________________________

My name is Aniela Ruszel-Parkitna. I was born in Poland in 1909. Until 1940, my family owned and farmed land at Anielowka, a village close to Ternopol in the south-east of Poland.

The Germans invaded Poland from the west on 1 September 1939, and the Russians invaded from the east on 17 September 1939. They divided Poland between them. In the Russian-controlled area, the plan to ethnically-cleanse the area soon took effect with the first of four mass deportations to Siberia that were carried out in 1940 and 1941.

On 10 February 1940, Russian soldiers and Ukrainians came on sledges in the middle of the night and told us to pack what we could carry and that we had to leave.All the houses in the village were set alight and the animals burned. My sister, Albina, was allowed to stay because she was married to a Ukrainian.

We were all packed into a train of cattle wagons, and we set off on a very long journey that lasted three weeks. We eventually arrived at a place called Murashi, on the fringes of western Siberia. There, we were herded onto sledges and carried for another 100km to a place called Noshul. It was freezing cold and there was very deep snow.

Noshul was a lumber camp. Trees was cut and hauled (probably to supply mining props). Much coal was, and still is, mined in this region.

There were cabins for us to live in, and at least these were warm, as we had much wood to burn and we had stoves in the cabins. The beds were made from wooden boards, but there was no bedding to sleep on. We were each given 300g of bread per day and boiled water to drink with it. We spent one week doing nothing at all, then the men were made to go and cut the trees while the women had to split the logs and keep the snow cleared from the roadways so that the tractor could come in and haul the logs. In the summer, the women had to remove the small branches from the felled trees and cut logs into one-meter lengths with big saws.

There was an epidemic of typhoid fever in the camp. One cabin became a makeshift hospital. I became very ill with the fever and many people died. Every time a

Polish person died, the Russian nurses would laugh and say, “Ah well, he’s gone back to Poland.”.

In June1941, Hitler broke his pact with Stalin and invaded Russia. This led to the signing of the Sikorski-Majewski agreement that called for the freeing of Poles imprisoned in POW camps and labour camps in the USSR, and the formation of a Polish Army in the southern USSR.

We left Noshul, but my sister Maria and her family stayed, saying that they hoped to return to Poland. They were repatriated to Poland in 1946. I did not see them again until 1964, when I went to visit Poland, I met Maria and some of her surviving family there.

My father Valenty and my mother Anna left Noshul with me. All the fit men volunteered to join the Polish Army to fight Hitler.

It took us two days to walk back to Murashi, pulling a sledge on which we had packed our few belongings and some dried mushrooms and berries to eat. We arrived at Murashi at night, and I was so tired that I was falling asleep standing up. We all slept in a big hall. In the morning, we were herded into cattle wagons, supervised by the Russians.

We were on this train journey for between three and four weeks (I am not sure) to a place in Uzbekistan called Dekanabat. My sister Zuzia was taken somewhere else, and I never saw her again. She and most of her children died somewhere in Uzbekistan.

There were many Jewish people with us at Dekanabat. We lit fires and cooked grain to eat. Some Uzbeks came with horses and donkeys and said that they were for the Polish people only. We were told we were leaving. Those without horses had to walk.

We walked all night to a large collective farm where we were told we had work. We were put into stables to live. The stables had been cleaned out and we had fires to keep warm.

It was Christmas Eve 1941, and we were all sitting round fires on the floor. Some were crying – many sang carols. My mother, Anna, was very ill with dysentery but still managed to prompt others when they forgot the words of the carols or songs. On Christmas Day we were taken to the ‘boss who gave us 300g of flour each. The next day my mother died of dysentery in my arms. We wrapped her body in sheets and buried her in the Uzbek cemetery.

I also had the dysentery, and I expected not to live, but I was lucky and recovered.

We worked on the farm until March 1942 and then typhoid fever broke out and almost everyone was very ill. My father Valenty died soon after this.

I caught typhoid and was in a coma for four days. I remember lying on hay in the corner of a barn and I realized I had recovered but could not use my legs. One of the other women used to pull me out into the sunshine to warm me during the day and then pull me back in at night. That same woman’s son went into Dekanabat to see the Polish doctor there who gave him some ointment. I rubbed this on my legs and I was eventually better.

In the spring of 1942, we were still all working on the farm, picking pests off the grain crops by hand. We each had a a grain ration of 1 liter each. But we were also sieving grain as part of our work and much grain got stolen by all of us and used. We had the use of a mill on the nearby river and could make flour and cook placki - they resemble an Indian chapati bread.

In June 1942, we heard from the Polish doctor in the town that we were to be moved again. In July, we were made to walk to Dekanabat and assemble in the barracks there. Many of the Polish soldiers had died of dysentery but some remained. While in the barracks there was an outbreak of malaria. We all caught this, but luckily, a Polish nursing sister gave us quinine, and we did recover. We had to register for transport and there were large queues to do this.

When we had registered, we were taken to the station to catch a train for Krasnowodsk, but we spent three weeks on the station platform waiting for the train to come. The train, when it came, took us to Krasnowodsk in western Turkmenistan.

We boarded a ship from there and sailed across the Caspian Sea to a place called Pahlevi in Persia (now Iran). There were Polish soldiers protecting us on the ship and we all had to pretend to be well even if we were ill because we had been told that only the healthy ones would be taken out of the USSR. While the soldiers took the sick away to hospital, we bathed in the Caspian Sea and were very happy at this time. We got food and tasted meat for the first time since the invasion of our village. It was lamb and we were so unused to it that we all got terrible stomach aches!

We were in Pahlevi for two weeks and then we boarded trucks for Tehran, the capital. We had mattresses and food. We cooked traditional Polish food including kluski (a form of pasta) and we had apples and good bread. We also received parcels from America with dresses, shawls and blankets. I cannot remember how long we were in Tehran, but I think it must have been about a month.

From there we went to a place called Ahvaz and we lived in stables for about three weeks while we waited to board the ship which would take us all to Africa. There were stories going round that the sea was mined and that this was a very dangerous journey. We were all quite scared about this. When the time came to board the ships, I was among those on the very first ship to leave. We had four other ships escorting us and the crossing was without incident. (It is highly probable that the Straits of Hormuz were, in fact, mined to prevent Allied oil shipments leaving Basra and that the ‘four other ships were minesweepers based in the Gulf.)

I am not certain where we docked in Africa, but I remember that we passed the big waterfalls called Victoria on the train to Lusaka in Northern Rhodesia, which was a British colony at this time. (Aniela’s likely port of disembarkation was Beira in Mozambique, as this appears to be the only railhead linking with Lusaka, in what is now Zambia, that offers a route past the Victoria Falls). Every time the train stopped, many black people tried to approach the train, but they were kept away by police with truncheons.

We stayed in a settlement outside Lusaka which was for Polish people only. We saw homes of many English people who seemed to be very rich. In the Polish settlement there was one hut for every four people, and there was a communal kitchen and four dining rooms. The huts were made of a sort of brick made from mud, with straw roofs. During my stay in Lusaka, I caught malaria again, twice. I worked in a hospital, sewing sheets and doubling sheets.

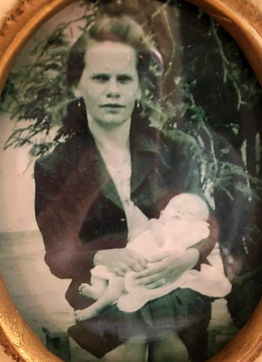

Later I met an Italian man who had been a prisoner-of-war, and we fell in love. Our daughter Lidia was born on 2 September 1946 in Lusaka.

The Polish soldiers fought for the Allies on every front, but they died for nothing. Poland was partitioned and a communist government was installed. All the people in the Polish settlement vowed never to return until Poland was free again.

Churchill had agreed to accept Polish refugees: some to England and some to Australia. So in October 1948, I arrived in England with my daughter. We went to a hostel in a place called Daglingworth in the north of England. Lidia got very ill with bronchitis.

We soon moved to another settlement in Marsworth, near Tring in Hertfordshire in the southeast of England. There I met and married Jozef Parkitny who was a Polish soldier, injured in the war and living in London near Baker Street. Here I also met up again with my brother Franciszek, who had been in the Polish army.

My younger daughter Krystyna was born on 9 November 1952. In 1955, my husband Jozef died from leukemia.

I worked in nearby Berkhamsted, sewing coats in a garment factory. In 1961 the Marsworth Polish hostel was closed, and I moved into a council house in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire.

Source: www.marsworth.org.ukmarsworth-polish-hostel

Aniela with Lidia in Africa

Aniela with Krystyna in pram and Lidia in UK

Aniela Ruszel-Parkitna

Copyright: Aniela Ruszel-Parkitna